Tha òran snog ainmeil tradaiseanta ann air a bheil Dh’èirich mi moch madainn Chèitein. ‘S e òran-luaidh a th’ ann, luath, beòthail, aighearach, làn molaidh air na h-eòin ‘s an ceilearadh, air a’ bhradan a’ leum, agus air àilleachd nàdair. Ann an cuid de na tionndaidhean, tha nuallan a’ chruidh a’ nochdadh, is banarach bhòidheach a’ dol dhan bhleoghan. ‘S e dealbh eireachdail a th’ ann, agus nuair a chluinneas tu an t-òran, no gu h-àraid ma ghabhas tu thu fhèin e, bidh thu a’ faireachdainn toilichte, dòchasach, sìtheil, fada air falbh bhon t-sluagh agus saor o dhraghan an t-saoghail.

Ach san darna leth den 19. linn, aig àm na strì airson còraichean nan croiteirean, nochd faclan eile air an aon fhonn – faclan politeagach. An turas seo ‘s e moladh air duine a th’ ann seach air nàdar, is esan Teàrlach Friseal Mac an Tòisich, neach-lagha a sheas airson nan croiteirean, sgrìobhaiche is òraidiche gun sgìos, ball den Choimisean Napier – agus neach-iomairt sgairteil airson cleachdadh na Gàidhlig anns na sgoiltean (toirmisgte aig an àm sin), mar chànan co-ionnan ri Beurla. ‘S e seo a tha ga chomharrachadh san tionndadh ùr den òran.

B‘ e duine comasach buadhach a bh’ ann, agus araidh air òran le cinnt. Agus nochd e gu dearbh ann am fear eile, le Màiri Mhòr nan Òran fhèin, a chuidich e, a rèir coltais, nuair a bha i fo chasaid mèirle breugaich. ‘S ann a thaing aigesan cuideachd a chaidh Leabharlann Saor Poblach ann an Inbhir Nis a a stèidheachadh ann an 1883, gus cothrom a thoirt do gach neach foghlam is fiosrachadh fhaighinn gus nach biodh iad tuilleadh ann am muinghinn breugan an luchd-politigs no nan uachdaran.

Mar sin, nuair a chomharraicheas sinn Là nan Còraichean Luchd-Obrach a’ chiad latha den Chèitean am bliadhna, bu choir dhuinn a bhith a’ smaoineachadh cuideachd air na gaisgich againn fhèin air a’ Ghàidhealtachd, a dh’oibrich airson nan còraichean againne – agus tha gu leòr ann dhiubh!

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

There’s a lovely traditional song called Dh’èirich mi moch madainn Chèitein (I arose early on a May morning). It’s a waulking song, fast, lively, joyful, full of praise for the birds and their singing, the salmon leaping, and the beauty of nature. In some versions there are also cattle lowing and a pretty milkmaid. It’s an idyllic picture, and when you hear the song, or particularly if you sing it yourself, you can’t help but feel happy, optimistic, peaceful, far away from the crowds and free of the worries of the world.

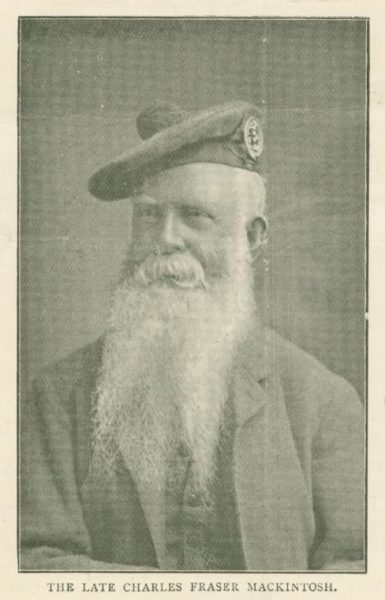

But in the second half of the 19th century, at the time of the struggle for crofters’ rights, another set of words appeared to the same tune – political words. This time it was praising a man instead of nature, and that man was Charles Frazer Mackintosh, a lawyer who stood up for the crofters, a tireless writer and speaker, a member of the Napier Commission – and a vigorous campaigner for the use of Gaelic in the schools (at that time forbidden), on an equal basis to English. This is what is being celebrated in the new version of the song.

He was an able, influential figure and most certainly worthy of a song. And indeed he appears in another one too, by Màiri Mhòr nan Òran (“Big Mary of the Songs”) herself, the poet and land-campaigner whom he apparently helped defend when she was wrongly accused of theft. It’s thanks to him too that a Free Public Library was founded in Inverness in 1883, to enable everyone to access education and information, so that they would no longer be at the mercy of lying politicians or landlords.

So when we celebrate International Workers’ Rights Day on the 1st of May this year, we should also spare a thought for our own Highland heroes who worked for our rights – and there are plenty of them!

DH‘ÈIRICH MI MOCH MADAINN CHÈITEIN

| Tionndadh tradiseanta: Dh’éirich mi moch madainn Chéitein, Fail ill é hill ù hill ó, Hiuraibh ó na hó ro éile Fail ill é hill ù hill ó. Mas moch an-diugh bu mhuich’ an dé e. ‘S binn a’ chòisir rinn mi éisdeachd. Smeòraichean air bhàrr nan geugan, Uiseagan os cionn an t-sléibhe. ‘S bòidhche fhiamh ‘s a’ ghrian ag éirigh, Madainn chiùin fo dhriùchd nan speuran, Bric air linneachan a’ leumraich. Leannaidh slàinte agus éibhneas Riùthasan a bhios moch ag éirigh. | Traditional version: I arose early on a May morning. If early today it was earlier yesterday. Sweet was the choir I listened to, thrushes on the tops of the branches, larks above the moor. Beautiful is the prospect, with the sun rising, a calm morning under the dew of the heavens, trout leaping in the pools. There will follow health and happiness for those who rise early |

| Tionndadh ùr: Dh’èirich mi moch madainn Chèitein Faill il o hill u ill o, Hiùraibh o ‘s na hòro èile Faill il o hill u ill o Chuala mise sgeul bha èibhinn Gun robh gaisgich dheas air èirigh A chur beatha ‘n cainnt na Fèinne Chaidh iad cruinn a ceann a chèile Thuirt iad gu robh chànan feumail Anns an sgoil cho math ri Beurla Siud an duine a rinn feum dhuinn Friseal Mac an Tòisich gleusta Togaibh luinneag agus sèist dha Àrdaichear e gus na speuran Leis na Gàidheil ‘s gach àite ‘n tèid e. | New version: I arose early one May morning I heard news which gladdened me That the able heroes had risen To put spirit in the language of the Feinne They had gathered together Declaring the language of use In the schools as well as English Now there was a man… Wise Fraser MacIntosh Sing songs and tunes for him Let him be praised to the heavens By the Gaels wherever he goes. |

Kathleen MacInnes (new version of lyrics):