A’ bruidhinn mu dhaoine / Talking about people

I’ve amassed a huge number of words describing people, or used to address people. Many of them came up again and again, from sources old and young, including ones I collected over the years from those no longer with us. That shows that the words and expressions clearly were, and in some cases still are, well-used. As ever, many thanks to all who have helped with this. Keep them coming!

The “Seaboard words” are given as spelled / pronounced to me or written down by contributors, so usually are roughly phonetic – locals should recognise them. The Gaelic words are given in brackets, their approximate pronunciation in italics. In Gaelic, and in the Seaboard words that come from Gaelic, the first syllable is always stressed (and on the Seaboard often lengthened) e.g. spàgach, splay-footed = SPAA-cach.

1.The young

Bumalair – a big male child, careering around; a very big baby. What a bumalair! Also someone who messes up a job. (bumalair – bungler, oaf)

A wee eeshan – a naughty child (fairly mild, humorous word). (isean – a young bird, a wee child, esp. a naughty one)

A wee trooster – a mischief, a rascal (stronger word). (trustair – usually a very negative word used for adults – a dirty brute, filthy fellow, but clearly not as strong here)

Sproot – a rascal (maybe related to sprùis – an imp, pron. sprooosh)

Ploachack – a plump little girl or baby, admiringly. (possibly from pluiceach -a plump, chubby-cheeked person; ploiceag– a plump-cheeked woman; pluic = cheek)

Pochan, pockan – small cute person (pocan – small chubby lad; short fellow, pron. poch-can)

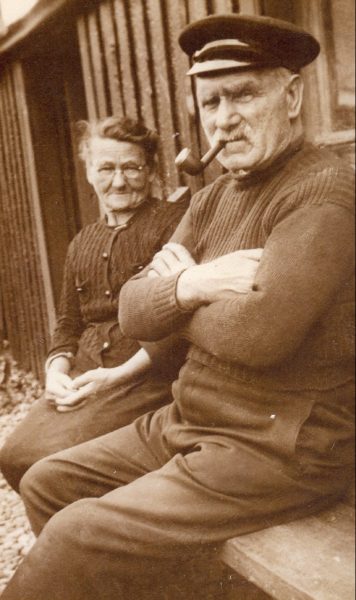

2.The old

Bodach, bottach, an old bottach – old man, old granda (bodach – old man)

Bo-ba – granda (not an “official” Gaelic word, but a common familiar term in at least Shandwick and Balintore)

Cailleach – an old wifie

3.Characteristics, physical features

Spacack, spagach – splay-footed (casan spàgach – splay feet)

Kervac – left-handed (from cearragach – left-handed, pron. kyarragach; cearrag, a left-hander)

Doikan – a small person (maybe connected to tòican – a small swelling, bump?)

4.Complimentary

Jeechallach – diligent, hard-working (dicheallach – diligent)

Spatchal – smart (spaideil – smart, pron. spatchal)

spatchack – posh (probably a variant of spaideil)

Ji-shall (pron. JA-ee-shal) – good, posh (probably from deiseil – ready, prepared; deiseal – sunwise, southward, lucky, prosperous: both pron. jay-shal)

5.Less complimentary (a long section!)

He’s no yolach … he’s not handy at what he’s doing; clueless (eòlach – knowledgeable)

Poor gilouris! Poor soul! (diolaoiris – object of charity (word recorded in Wick area); related to more common expression dìol-deirce – poor soul, wretch). Interestingly, one contributor’s father applied this term to a gallus youth.

Luspitan – weak, underfed individual (luspardan – dwarf; puny man)

I’m no voting for them – they’re no but greishers – very derogatory term. Probably comes from greis, a spell of time, a while – perhaps in the sense of time-servers, or fly- by-nights? There is also a word greiseachd – enticement, solicitation, so maybe greishers were persuasive speakers with nothing behind it? I think I’ll adopt this as my new term for politicians…

I’m in luperique – clothes or hands in a mess, e.g. if you spilled something on yourself or someone else. (Probably from (s)lupraich – slurping, wallowing, splashing, or possibly(s)luidearachd, slovenliness . The Seaboard sometimes dropped that initial S in words. (Probably because in some grammatical contexts in Gaelic, the S is changed to SH and not pronounced.)

Emmitchach -foolish (amaideach – foolish, pron. amajach)

Gorach – daft (gòrach – foolish)

Him, he hasn’t moochoo! He has no sense. (mothachadh –perception, awareness. Pron. mo-a-chugh or mo-a-choo)

In or on the artan – on your high horse, angry. (àrdan – arrogance, haughtiness; height, prominence)

Prawshal– stuck-up ( pròiseil – proud, pron. praw-shal)

Hanyel e gleek – he’s no wise (chan eil e glic)

Putting on the sglo – sweet-talking, buttering up. (sgleò – sheen, misting over; idle speech, verbiage.)

Beeallach – two-faced, untrustworthy (beul=mouth > beulach -smooth-talking, plausible, pron. bee-a-lach)

Glacker – person speaking foolishly (glacaire – a blusterer)

Awshach – a foolish woman (òinseach – female fool) – heard in Inver

Keolar – peculiar (ceòlar – peculiar, eccentric)

Glaikit – daft . (Old Scots, probably related to Gaelic gloic – a fool, gloiceach – foolish)

6.Endearments

Maytal – dear, pet (m’ eudail – my dear, pron. may-tal)

Brogach, a term of endearment for a wee boy (brogach – a sturdy lad)

Moolie – pet, darling (to a child) (m’ ulaidh – my treasure)

Ma geul – my love (mo ghaol)

7.Feelings

If I lift my drochnadar… – if I lose my temper, look out! (droch nàdar – bad temper)

Fyown – feeble, feeling flat, dispirited, faint. (fann – weak, faint, pron. fown, or feann, shortening, diminishing, pron. fyown)

Rohpach – feeling ropach – rough (ropach – in poor condition, scruffy, pron. roppach; ròpach – tangled, untidy, pron. roh-pach)

Brohnach – sad (brònach)

In a stoorsht – in a huff, in a fit of pique (stuirt – huffiness, pron. stoorsht)

Have a boos on you – sulk, pout (bus -pout, pron. booss)

Boossoch – grumpy (busach)