Cuairt Drochaid an Airgid

Tha sibh uile eòlach air Eas Rothagaidh, eadar Cunndainn is Gairbh air rathad Ulapul, far am bi tòrr dhaoine a’ dol as t-samhradh an dòchas na bradain fhaicinn, is iad a’ leum suas an eas san Alltan Dubh gus an grunnd-cladha a ruigsinn. Chan eil a’ chuairt sin ach 20 – 30 mionaid gus coiseachd dhan eas, dealbhan a thogail bhon drochaid-chrochaidh, is air ais dhan àite-parcaidh, agus cuairt bhrèagha a th’ ann gun teagamh. Ach tha cuairt eile ann nach eil cho fada air falbh bho Rothagaidh, agus ceart cho àlainn nam bheachdsa, ged nach bi an uiread de dhaoine a’ dol ann cho tric idir. An-diugh tha mi an dòchas ur brosnachadh a dhol ann, le dealbhan is beagan fiosrachaidh. ‘S urrainn dhuibh cuideachd an dà chuairt a dhèanamh san aon mhadainn no fheasgar.

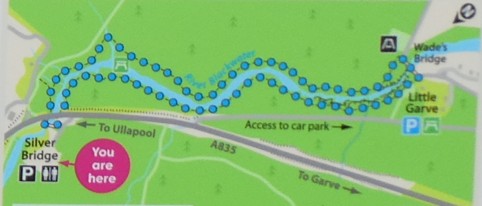

Dràibh mu 10 mionaidean nas fhaide slighe Ulapul (A835) tro Ghairbh, seachad air dealachadh an rathaid gu Geàrrloch is Caol (taobh clì), agus seachad air soidhne-rathaid “Little Garve” (taobh deas), agus tionndaidh ri do làimh chlì far am faic thu soidhne airson P agus taighean-beaga, dìreach ron drochaid-rathaid thairis air an Alltan Dubh. A-nis faodaidh tu ceum-cuairt mu 1 ¼ uairean a thìde a dhèanamh, le bhith a’ cleachdadh dà dhrochaid eachdraidheil.

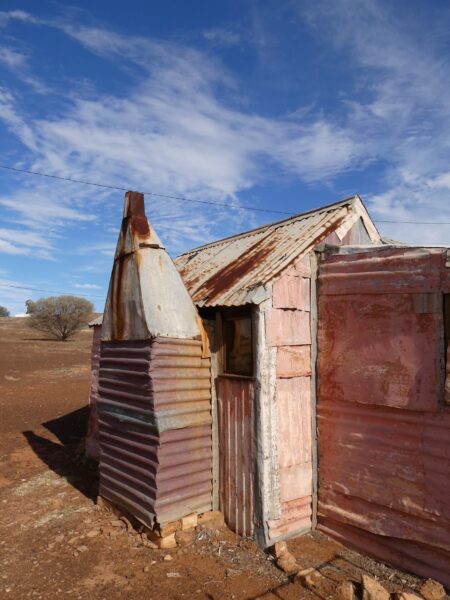

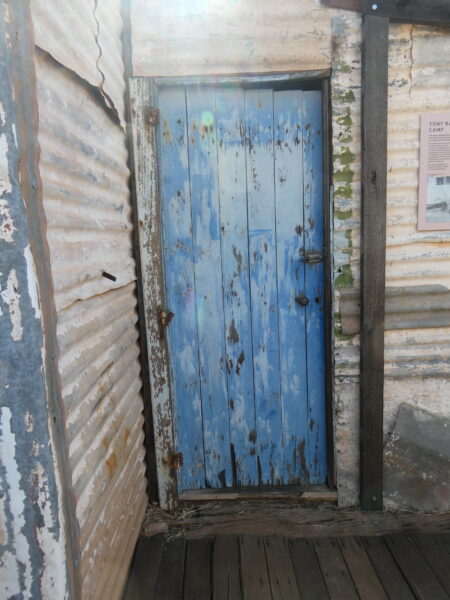

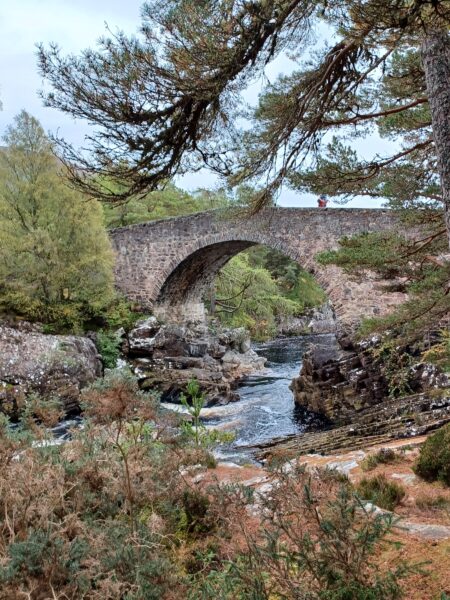

Tòisich aig an àite-parcaidh agus coisich beagan cheumannan air ais a dh’ionnsaigh an rathaid, agus chì thu soidhne le fiosrachadh feumail is inntinneach mu Dhrochaid an Airgid, ainm a th’ air an drochaid seo air sgàth nam mìrean mìoca a’ boillsgeadh sa chreag-lathaich ghlas. A-nis tionndaidh ri do làimh chlì agus rach air an t-seann drochaid fhèin. Chleachdadh na dròbhairean an drochaid seo air an slighe chun nam margaidean mòra nas fhaide deas. Feumaidh gun do mhùch geumnaich is stampadh nan ceudan de chrodh tàirneanach nan easan fon drochaid. Bidh sealladh dràmadach agad a’ coimhead suas an Alltan Dubh, le sreath easan geala is ruadh-dhonn – dath na mòna – eadar na clachan dorcha.

Air an taobh eile, tionndaidh ri do làimh dheis, a’ dol sìos chun a’ ceum fon drochaid-rathaid ùr. Seall air ais tro Dhrochaid an Airgid airson seallaidh bhrèagha eile de na h-easan air am frèamadh leis a’ bhogha. A-nis cum ort air a’ cheum fad mu 30 mionaid, a leantainn an abhainn leis an t-sruth. An toiseach bidh thu a’ dol suas is sìos airson beagan cheudan de shlatan, agus pìos air falbh bhon abhainn, ach cluinnidh tu fad na h-ùine i. Thèid thu thairis air allt le easan boidheach air drochaid fhiodha bheag, agus chì thu rainich is còinnich eadar-dhealaichte agus ‘s dòcha sòbhraich, sailean-cuach, is flùraichean na gaoithe as t-earrach. Às dèidh sin gluaisidh an ceum nas fhaisge air an Alltann Dubh a-rithist, agus fàsaidh e nas còmhnairde. Fad na h-ùine bidh thu a’ coiseachd eadar giuthais-Albannach òga, àrda, dìreach, ach le solas is rùm eadarra is iomadh lus no preas beag a’ fàs, gu h-àiridh caoran-mitheig, nam mìltean!

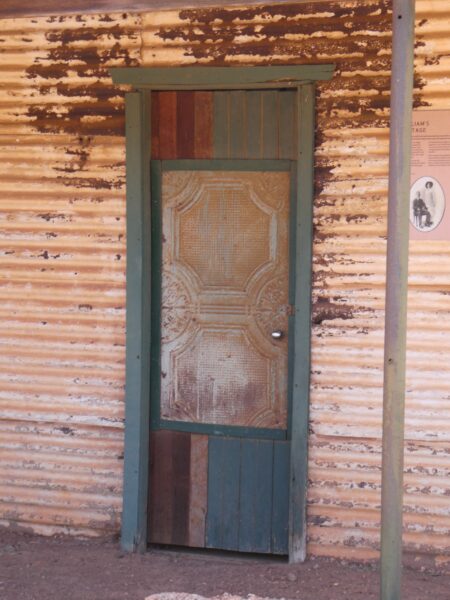

Ruigidh tu mu dheireadh seann drochaid chloiche eile, Drochaid Ghairbh Bhig, air a togail leis a’ Mhàidsear Caulfield ann an 1767 mar phàirt de phròiseact mòr togail rathaidean armailteach tron Ghàidhealtachd às dèidh aramachan nan Seumasach, air a thòisicheadh le Seanalair Wade. Seallaidhean àlainn an seo cuideachd, aon taobh na h-aibhne nas fhiadhaiche, an taobh eile nas ciùine.

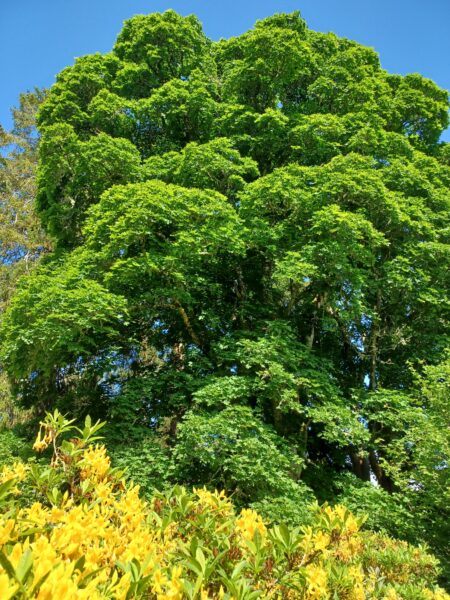

Rach thairis air an drochaid, tionndaidh ri do làimh dheis, agus till air ais gu Drochaid an Airgid, ris an t-sruth – mar na bradain. Chì thu coilich an t-struth cha mhòr fad na h-uine, is an abhainn a’ sabaid gu tartarach an aghaidh nam filleaidhean tomadach cloiche ag èirigh na slighe. Tha thu nas dhlùithe air an abhainn air a‘ bhruach seo, le cothroman dealbhan sònraichte àlainn a thogail. Coisichidh tu am measg ghiusach-Albannach fìor shean a-nis, le rùm gu leòr airson fàs mòr is leathann, le geugan trom, sgaoilteach, gu h-àraidh ri taobh na h-aibhne. Tha an ceum nas nàdarra air an taobh seo, le freumhan is uaireannan clachan fo do chasan, ach, nam beachdsa, nas brèagha.

Às dèidh mu 1 ¼ uairean a thìde is 2 ½ mìle uile gu lèir tha thu air ais aig an àite-parcaidh – agus le cinnt deiseil mar dhuais airson reòteige blasta Black Isle Dairy ann an Srath Pheofhair air an rathad dhachaigh!

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Silverbridge walk

You all know Rogie Falls, between Contin and Garve, where lots of people go in summer in the hope of seeing the salmon leaping up the waterfall on the Blackwater river to reach their spawning grounds. That walk is only about 20-30 minutes to walk to the waterfall, take photos on the suspension bridge, and back to the carpark, and it’s a lovely walk without a doubt. But there’s another walk not so far from Rogie, and just as lovely in my opinion, although not so many people go there so often at all. Today I’m hoping to encourage you all to go there, with pictures and some information. You can also combine the two walks in the same morning or afternoon.

Drive on about 10 minutes along the Ullapool road (A835) through Garve, past the junction to Gairloch and Kyle (on the left) and the sign to Little Garve (on the right), and turn left where you see the sign for P and toilets, right before the road bridge over the Blackwater. Now you can do a circular walk of about 1 ¼ hours, using two historic bridges.

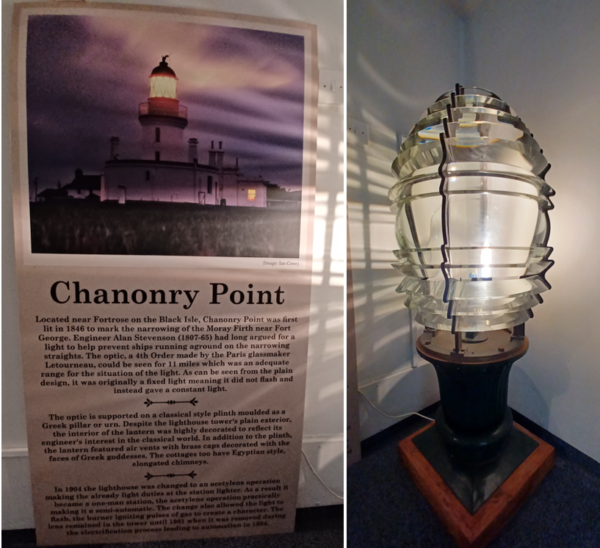

Start at the car park and walk back a few steps towards the road, and you’ll see a sign with useful and interesting information about Silverbridge, the name given to this bridge because of the specks of mica sparkling in the dark schist. Now go left onto the old bridge itself. The cattle drovers used this bridge on their way to the big markets further south. The bellowing and stamping of the hundreds of cattle must have drowned out the thunder of the waterfalls below the bridge. You have a dramatic view up the Blackwater, with a string of white and tawny rapids – the colour of the peat – between the dark rocks.

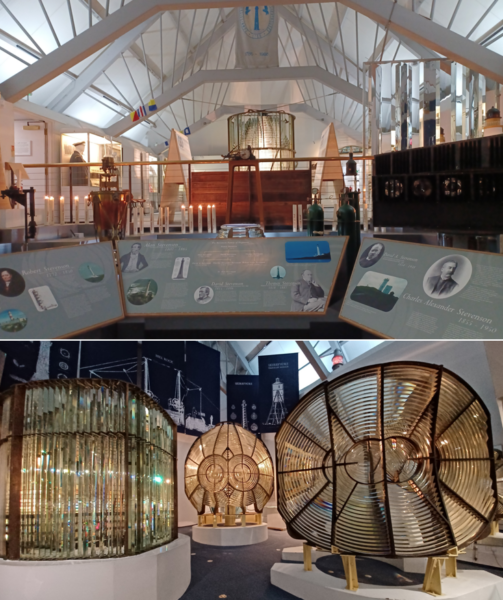

On the other side, turn right, going down to the path under the new bridge. Look back through Silverbridge for another lovely view of the falls, framed by the arch. Now carry straight on on the path for about half an hour, following the river downstream. At first you go up and down somewhat for a few hundred yards, and a bit away from the riverside, but you’ll hear it all the time. You cross a burn with pretty waterfalls on a small wooden bridge, and you’ll see a variety of ferns and mosses, and maybe primroses, dog-violets and wood anemones in spring. After that the path moves back nearer the Blackwater again, and gets flatter. You’re walking the whole time between tall, straight young Scots pines, but with light and space between them, and many plants and small bushes growing there, especially blaeberries – in their thousands!

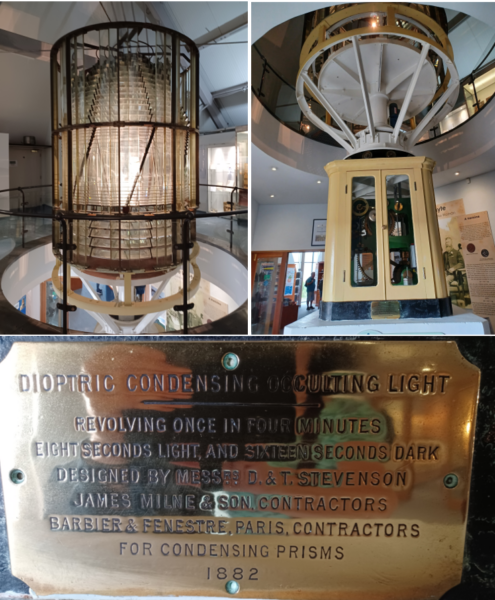

You finally reach another old stone bridge, Little Garve Bridge, built by Major Caulfield in 1767 as part of a huge project to build military roads through the Highlands after the Jacobite risings, begun by General Wade. Beautiful views here too, one side of the bridge wilder, the other side more serene.

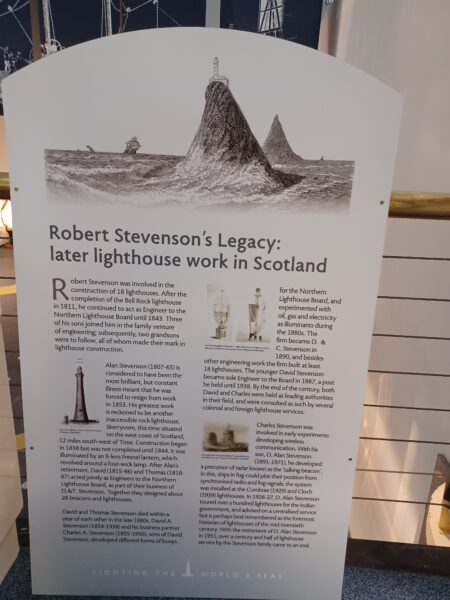

Cross the bridge, turn right, and head back to Silverbridge against the stream – like the salmon. You’ll see rapids almost the whole time, the river fighting noisily against the massive layers of rock rising in its path. You’re nearer the the river on this bank, with opportunities to take especially beautiful photos. You’re walking among really old Scots pines now, with enough room to grow big and broad, with heavy spreading branches, especially beside the river. The path is more natural on this side, with roots and sometimes stones underfoot, but, in my opinion, prettier.

After about 1 ¼ hours and 2 ½ miles altogether, you’re back at the carpark – and definitely ready to reward yourself with a delicious Black Isle Dairy ice-cream in Strathpeffer on the way home!

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++