An Eala Bhàn

Bha mi aig Celtic Connections ann an Glaschu seachdain no dhà air ais agus am measg chuirmean-ciùil eile bha mi aig oidhche mhòr san Talla Consairt Rìoghail, Òrain nan Gàidheal. Ghabh Gillebrìde Mac ‘Ille Mhaoil An Eala Bhàn, òran ainmeil air a sgrìobhadh ann an trainnsichean an Somme rè a‘ Chogaidh Mhòir. Leis gu bheil sinn a‘ comharrachadh ceud bliadhna o dheireadh a‘ chogaidh sin am-bliadhna, bha e gu sònraichte drùidhteach na faclan sin a chluinntinn a‘ cur an cèill faireachdainnean is smuaintean duine òig anns an t-suidheachadh oillteil sin fad‘ air falbh bho dhachaigh.

Bha mi aig Celtic Connections ann an Glaschu seachdain no dhà air ais agus am measg chuirmean-ciùil eile bha mi aig oidhche mhòr san Talla Consairt Rìoghail, Òrain nan Gàidheal. Ghabh Gillebrìde Mac ‘Ille Mhaoil An Eala Bhàn, òran ainmeil air a sgrìobhadh ann an trainnsichean an Somme rè a‘ Chogaidh Mhòir. Leis gu bheil sinn a‘ comharrachadh ceud bliadhna o dheireadh a‘ chogaidh sin am-bliadhna, bha e gu sònraichte drùidhteach na faclan sin a chluinntinn a‘ cur an cèill faireachdainnean is smuaintean duine òig anns an t-suidheachadh oillteil sin fad‘ air falbh bho dhachaigh.

Chaidh an t-òran a sgrìobhadh le Dòmhnall Dòmhnallach, nas aithnichte mar Dhòmhnall Ruadh Chorùna (1887 – 1967), à Uibhist a Tuath, agus e a’ smaoineachadh air a leannan, Magaidh NicLeòid. Mar a b‘ àbhaist aig an àm, cha do dh‘ionnsaich e Gàidhlig a sgrìobhadh aig an sgoil agus mar sin bha aige (agus aig iomadh bàrd eile) ri a chuid bàrdachd a chruthachadh agus a chumail sa cheann – euchd drùidhteach dhuinne an-diugh, agus sgaoil e fhèin i aig cèilidhean agus am measg chàirdean, anns an dòigh thraidiseanta. Mar sin dh’fhàs e ainmeil, gu h-àraidh mar bhàrd-cogaidh, fada mus do nochd a‘ chiad leabhar den bhàrdachd aige ann an 1969, air a tar-sgrìobhadh bho Dhòmhnall fhèin le Seonaidh Ailig Mac a‘ Phearsain, sgoilear Gàidhlig a bha na neach-teagaisg ann an Uibhist aig an àm.

’S e òran gu math fada a tha anns An Eala Bhàn, ach tha mi airson blas beag dheth a thoirt dhuibh. Tha a’ chiad rann a’ toirt an cuimhne an t-eilean agus an dòigh-beatha a dh’fhàg e:

Gur duilich leam mar tha mi ‘s mo chridhe ‘n sàs aig bròn

Bhon an uair a dh’fhàg mi beanntan àrd a’ cheò

Gleanntanan a’ mhànrain, nan loch, nam bàgh ‘s nan òb

‘S an eala bhàn tha tàmh ann gach latha air ‘m bheil mi ‘n tòir.

‘S i an eala bhàn an dealbh as treasa an seo, seòrsa samhla den t-saoghal shlàn, chiùin, nàdarrach a bha aige agus e ann an saoghal gu tur eadar-dhealaichte a-nis, ach cuideachd ìomhaigh den chaileig òig a dh’fhàg e. Tha e ag obair le dealbhan cumhachdach air feadh an òrain, m.e. fuaimean a’ bhlàir:

Tha ‘n talamh lèir mun cuairt dhìom na mheallan suas sna neòil

Tha ‘n talamh lèir mun cuairt dhìom na mheallan suas sna neòil

Aig na shells a’ bualadh – cha lèir dhomh buan le ceò;

Gun chlaisneachd aig mo chluasan le fuaim a’ ghunna mhòir…

no nuair a tha e a’ cur an cèill na faireachdainnean aige aig dol fodha na grèine:

Tha mise seo ‘s mo shùil an iar on chrom a’ ghrian san t-sàl;

Mo bheannachd leig mi às a dèidh ged thrèig i mi cho tràth,

Gun fhios am faic mi màireach i nuair dhìreas i gu h-àrd…

no a’ bruidhinn mun chianalas:

Tha m’ aigne air a lionadh le cianalas cho làn ‘S a’ ghruag a dh’fhàs cho ruadh orm a-nis air thuar bhith bàn.

Tha e a’ feuchainn ri sòlas a thoirt do Mhagaidh – agus dha fhèin, le dealbhan is faclan às a’ Bhìoball, ach a’ toirt gu cuimhne a dhùthaich cuideachd:

A Mhagaidh na bi tùrsach, a rùin, ged gheibhinn bàs

Cò am fear am measg an t-sluaigh a mhaireas buan gu bràth

Chan eil sinn uile ach air chuairt mar dhìthein buaile dh’fhàs

Bheir siantanan na bliadhna sìos ‘s cha tog a’ ghrian an-àird.

Agus aig deireadh an òrain is iad seo na dealbhan uile – gaol, dachaigh, an cogadh – a tha e a’ tarraing ri chèile ann an “Oidhche mhath leat” brònach deireannach:

Oidhche mhath leat fhèin a ghaoil nad leabaidh chùbhraidh bhlàth

Oidhche mhath leat fhèin a ghaoil nad leabaidh chùbhraidh bhlàth

Cadal sàmhach air do shùil ‘s do dhùsgadh sunndach slàn

Tha mise ‘n seo san trainnsidh fhuar ‘s nam chluasan fuaim a’ bhàis

Gun dùil ri faighinn às le buaidh tha ‘n cuan cho buan ri shnàmh.

Tha fios againn gun do thill e air ais, ach mar dhuine atharraichte, làn brisidh-dhùil. Cha do phòs e a Mhagaidh agus cha d’ fhuair e (no duine eile) am fearann a bha air a ghealltainn dha na saighdearean leis an riaghaltas. Ach rè nam bliadhnaichean thàinig piseach air a bheatha; phòs e boireannach eile agus fhuair e obair mar chlachair. Agus lean e air leis a’ bhàrdachd.

Chan e na dealbhan agus na beachdan a-mhàin a tha cho cumhachdach, is i an dòigh-sgrìobhaidh cuideachd – tha e a’ peantadh le fuaimean agus uaithnean traidiseanta na bàrdachd Gàidhlig. Agus tha am fonn brèagha a’ toirt lùth is dathan a bharrachd dha na faclan. Is beag an t-iongnadh gu bheil luchd-ciùil cho measail air an òran – tha e air a chlàradh le iomadh seinneadair, leithid Calum Ceanadach is Julie Fowlis.

Seo dà chlàradh air a bheil mise measail, fear ann an dòigh thràidiseanta le Ùisdean MacMhathain à Uibhist a Tuath (le faclan G+B gu h-ìosal): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=30dWUIHJoFM

agus fear eile ann an dòigh nas ùire, ach drùidhteach fhèin, le Karen NicMhathain (Capercaillie): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSyYb9jO7vQ

Barrachd fhaclan: http://www.celticlyricscorner.net/capercaillie/aneala.htm (G+B), agus http://www.bbc.co.uk/alba/oran/orain/an_eala_bhan/ (G)

*****************************************************************

An Eala Bhàn / The Fair Swan

I was at Celtic Connections in Glasgow a couple of weeks ago and attended a great Concert in the Royal Concert Hall, Songs of the Gaels. There Gillebride Macmillan sang the famous song An Eala Bhàn, the Fair Swan, written in the trenches at the Battle of the Somme during World War 1. With this year being the 100th anniversary of the end of that war, it was particularly moving to hear the thoughts and feelings of a young man in that horrific situation, far away from home.

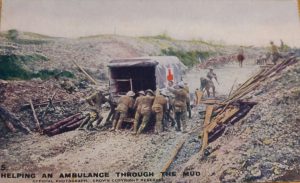

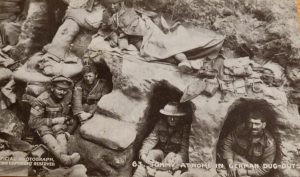

I was at Celtic Connections in Glasgow a couple of weeks ago and attended a great Concert in the Royal Concert Hall, Songs of the Gaels. There Gillebride Macmillan sang the famous song An Eala Bhàn, the Fair Swan, written in the trenches at the Battle of the Somme during World War 1. With this year being the 100th anniversary of the end of that war, it was particularly moving to hear the thoughts and feelings of a young man in that horrific situation, far away from home.

The song was written by the North Uist poet Donald Macdonald, “Dòmhnall Ruadh Chorùna” (red-haired Donald of the village of Coruna), for his sweetheart, Maggie Macleod. As was the rule at that time he didn’t learn to write Gaelic (his mother tongue) at school, so he had to compose and remember all his poems by heart (what a feat of memory to us today), and recite or sing them at ceilidhs and friends’ houses in the traditional way. So he became famous, especially as a war-poet, long before his first book of poems was published in 1969, transcribed directly from Dòmhnall by Gaelic scholar Johnny Alec Macpherson.

The song has lots of verses but I’ll try to give you a wee flavour of it here.

Verse 1: Sad as I am, my heart seared with sorrow, Since I left my misty high mountains, the glens where we courted, The lochs, bays and stromes, and the fair swan who dwells there and whom I constantly pursue.

The ‘fair swan’ is his most striking image, and is a sort of symbol of the wholesome, calm, natural world he has left behind for this cruelly different one, but also an image of his fair young innocent Maggie.

He works with such pictures throughout the song, e.g. the sounds of war:

The ground around me is like hail up in the sky, With shells crashing, I can see nothing for smoke. My hearing has gone with the noise of the big guns….

Or when he expresses his feelings at each sunset:

Here I am with my eyes towards the west since the sun sank into the sea; I sent my blessing with her though she left too soon, Without knowing if I would see her again tomorrow.

Or speaking about his longing for home:

My spirit is so full of longing that my once-red hair is almost white.

He tries to comfort Maggie – and himself – with words from the Bible, but also calling to mind his native landscape:

He tries to comfort Maggie – and himself – with words from the Bible, but also calling to mind his native landscape:

O Maggie, don’t be sad, love, if I should die. Which of us lives for ever? We are all just passing though, like flowers in the cattle-fold That this year’s elements will flatten and that the sun won’t raise again.

At the end of the poem he draws together these strands – love, his home, the war – in a sad “last goodnight”.

Goodnight my love in your warm fragrant bed, Peaceful sleep to you, and may you awake healthy and cheerful. I am here in the cold trench with the clamour of death in my ears, Without hope of returning victorious – that ocean is too wide to swim.

We know that Dòmhnall did actually return, but a changed, disillusioned man. He didn’t marry his Maggie, and he didn’t get the piece of land the government had promised him and the other soldiers. But in the course of time things improved for him. He married another woman, and found work as a stonemason – and continued to compose poetry.

It’s not just the word-pictures and the thoughts which are so powerful, it’s also the way he writes. He paints with sounds, and the traditional internal rhymes of Gaelic poetry. The beautiful melody adds even more strength and colour to the words. It’s no wonder that musicians are so fond of this song. It’s been recorded by countless singers, from Calum Kennedy to Julie Fowlis.

Here are two of my favourites, one traditional, by Hugh Matheson from N. Uist (with bilingual lyrics below): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=30dWUIHJoFM

Another good one by Mànran: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FTT_PyxTtTo

And a more modern one, but very expressive, by Karen Matheson of Capercaille: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSyYb9jO7vQ

More lyrics: http://www.celticlyricscorner.net/capercaillie/aneala.htm (Gaelic+English) http://www.bbc.co.uk/alba/oran/orain/an_eala_bhan/ (Gaelic )

Thanks to Catherine Mackay, Invergordon for the postcards from WW1.