Gwalia, Astràilia an Iar

Bha mi ann an Astràlia an Iar san t-Samhain, air cèilidh air mo bhràthair ann am Peairt, agus bha turas thairis air an Outback dha na Goldfields, na “Raointean Òir”, am measg nam fìor bhàrr-phuingean. Bha mi airson a dhol ann fad bliadhna no dhà, às dèidh dhomh dealbhan is aithrisean de bhaile Gwalia fhaicinn, is e aithichte mar “bhaile nan taibhsean”, dachaigh do mhèinneadairean na h-òr-mheinn “Sons of Gwalia” eadar 1896 agus 1963. ‘S e ainm litreachail air a’ Chuimrigh a th’ ann an Gwalia, is a’ chiad mhèinne bheag air a maoineachadh le dithis luchd-bùtha Cuimreach à Coolgardie. Tha am baile mu 830 mìle an ear air Peairt, ach fhuair mi a-mach gu bheil trèana sònraichte (is spaideil) ann eadar Peairt agus Kalgoorlie, am Prospector, seachd uairean a thìde aon slighe, agus le càr air mhàl, mu thrì uairean a thìde eile gu Gwalia. Dh’impich mi mo bhràthair a thighinn còmhla rium, agus thàinig esan agus companach eile. Sgioba Gwalia deiseil!

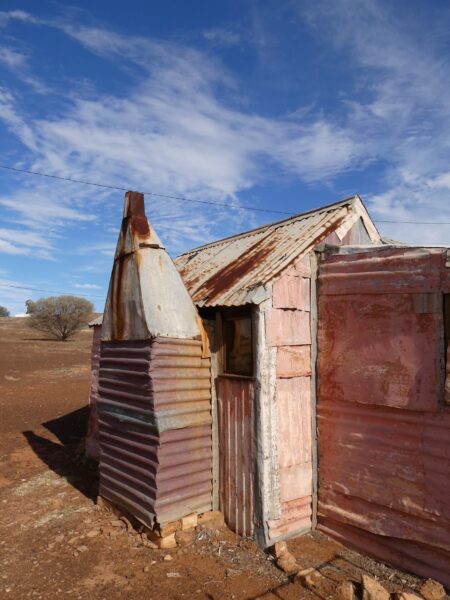

An rud as drùidhtiche ma dheidhinn, ‘s e gun do thog na mèinneadairean na taighean (no bothagan) iad fhèin, is iad a’ cleachdadh an stuth a bu saoire sa ghabhadh, gu h-àraidh iarann preasach, ach cuideachd pìosan fiodha bhochd, no uèir, no meatailt, no pìosan breige, rud sam bith a bha air fhàgail no air thilgeadh a-mach às an obair-mhèinne. Mar sin dh’fhàs baile gu lèir, an ceann ùine le bùth is òsdal is garaids is sgoil bheag, agus seòrsa taigh-seinnse neo-oifigeil (an “sly grog shop”), agus fiù ‘s taigh-osda/talla bhaile, an State Hotel, air a thogail leis an riaghaltas ann an 1903 mar phàirt sreath leithid de ghnothach sna Goldfields, le sùil ri casg a chur air taighean-òil mì-laghail. (Rud nach do shoirbhich buileach…)

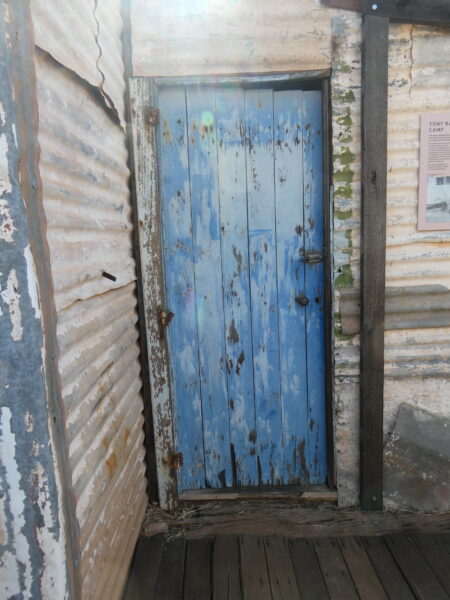

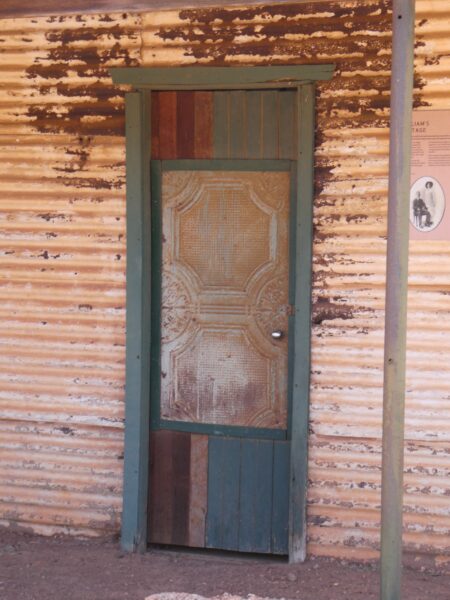

Chuir mi seachad ùine mhòr a’ dol a-steach dha na taighean is thog mi na ceudan de dhealbhan, a dh’aindeoin an teas is nan cuileagan. Chuir e drùidh orm dè cho innleachdach ‘s a bha iad, a’ cruthachadh taighean (gu tric do theaghlaich) à stuth cho bochd. Bha iad air an togail le beart simplidh fiodha is ballaichean is mullach à pìosan iarainn preasaich, le stòbha ann an aon seòmar, agus ‘s dòcha sacan heisean air am peantadh an àite pàipeir-balla. Reoth thu sa gheamhradh is ghoil thu as t-samhradh. Ach dh’fheuch iad ri am fàgail seasgair, snog, le plàideachan air am fighe, dealbhan à ìrisean, rudan beaga às an dachaighean fada air falbh. Chuir e iongantas orm gun do dh’fhuirich co-dhiù 500 daoine an sin, le ach glè bheag de leasachadh, gus dùnadh na mèinne ann an 1963. Daoine calma gu dearbh!

Bha baile eile na bu maireannaiche, Leonora, dà no trì mìle air falbh, far am biodh an luchd-rianachd na mèinne a’ fuireach, ach dha na mèinneadairean bha e na bu phractaigiche fuireach faisg air an obair. Ann an 1911 bha 1,114 daoine a’ fuireach ann an Gwalia. Chan e Breatannaich a-mhàin a bh’ annta (a’ phròifil in-imriche as luachmhoire) – bha eilthirich às an Roinn Eòrpa ann cuideachd, gu h-àraidh às an Eadailt is às an Iùgaslabh, far an robh an suidheachadh eaconamach sònraichte doirbh. Thàinig mòran dòchasaich à Sìona ann cuideachd ach rachadh leth-bhreith dhona a dhèanamh orra. Thill cuid de na h-in-imrichean dhachaigh, ach dh’fhuirich a’ mhòr-chuid fad ghinealach. M.e., b‘ e teaghlach Eadailteach nam Mazza a ruith a’ bhùth fad deicheadan.

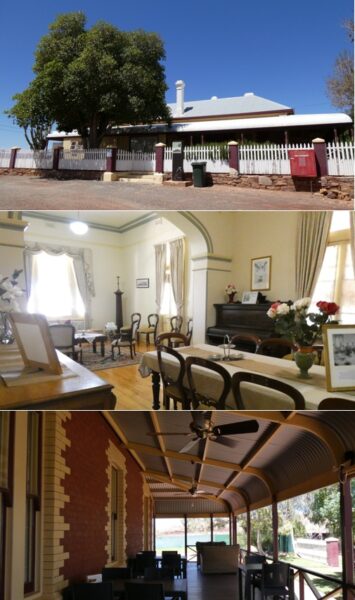

Uaireannan chaidh luchd-obrach Eadailteach no Iùgaslabhach a thoirt a-steach leis na ceannardan le tuarasdal na b’ ìsle nuair a bha na mèinneadairean a‘ bagradh a dhol air stailc airson barrachd airgid no chumhaichean-obrach na b’ fheàrr. Sin a rinn Herbert Hoover (ceann-suidhe nan SA 1929-33), is e na mhanaidsear-mèinne ann an 1898; gheàrr e na chòraichean-obrach agus na tuarasdail gu geur. (Ach cha robh bail air chosg a thaobh a’ phlana aige airson an taigh aige fhèin, faic gu h-ìosal…)

‘S e beatha gu math doirbh a bh’ aca uile gu lèir, agus anns an 1890an thàinig trioblaid eile orra – am fiabhras breac. Bhàs na mìltean anns na Goldfields, le suidheachadh slainteachais cho dona agus cus daoine is beathaichean a’ fuireach air an dinneadh ri chèile ann an campaichean mòra salach, mar aig Kalgoorlie, air “Mìle an Òir”. Thadail mi air cladh faisg air làimh agus bha e uabahsach faicinn an uiread de bhàsan òga aig an uair sin. Cunnartan na mèinne dhaibh gu h-ìosal agus cunnartan eile gu h-àrd, agus tìr gu math neo-mhathach mar dhachaigh. Mar a thuirt Hoover fhèin: “A land of red dust, black flies and white heat.”

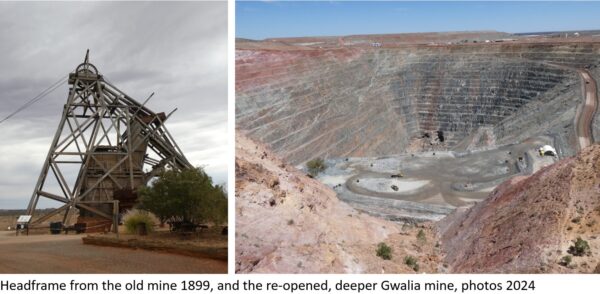

Tha taigh-tasgaidh na seann mhèinne faisg air a’ bhaile an diugh (tha a’ mhèinne air fhosgladh às ùr a-nis), agus dh’fheuch a’ choimhearsnachd mu thimcheall ri cuid de na taighean a dhìonadh is an àth-thogail. Fàgaidh mi sibh le cuid de na dealbhan – tha iad brònach, ach aig an aon àm àlainn (air an dòigh aca fhèin), ach barrachd is sin, tha na taighean nam fianais air nàdar is innleachdachd nan daoine fulangach sin sna bliadhnaichean tràth cruaidh.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Gwalia, West Australia

I was in West Australia in November, visiting my brother in Perth, and a trip out over the Outback to the Goldfields was one of the real highlights. I’d been wanting to go there for quite a while after seeing pictures and reports about the township of Gwalia, famous as a ”ghost town”, which was home to the gold-miners at the pit “Sons of Gwalia” between 1896 and 1963. Gwalia is a poetic name for Wales, as the original small mine was funded by two Welsh storekeepers from Coolgardie. The town is about 830 miles from Perth, but I found out that there is a special, rather posh train called The Prospector that runs from Perth to Kalgoorlie, about 7 hours one-way, and you can hire a car for the remaining 3 hours or so up to Gwalia. I persuaded my brother to join me and he came along with a pal – Team Gwalia was ready to go!

The most impressive thing about it is that the miners themselves built the “cottages” (or huts), using the cheapest material possible, especially corrugated iron, but also pieces of poor-quality wood, or wire, or metal, or bits of bricks – anything discarded or left over from the mining work. This turned into a complete township, in the course of time with a store, a hostel, a garage, a small school, a sort of unofficial pub (the “sly grog shop”), and even a hotel/village hall, the State Hotel – that was built by the government in 1903 as part of a chain of such establishments, aimed at cutting out the illegal drinking-houses (something that didn’t entirely succeed…).

I spent many hours going into each house and taking hundreds of photos, despite the heat, and the flies. I was struck by how ingenious they were, creating homes (often for families) from such poor materials. The cottages were built with a simple wooden frame, and walls and roofs of scrap pieces of corrugated iron, with a stove in one room, and sometimes painted hessian sacks instead of wallpaper. People would freeze in winter and boil in summer. But they clearly tried to make things cosy and homely with knitted blankets, magazine pictures on the walls, and small mementoes of their distant homelands. It seemed amazing that at least 500 people were still living there, with very little development, till the mine closed in 1963. A tough lot indeed!

There was another more permanent settlement a couple of miles away, Leonora, where the mine administrators lived, but it was more practical for the miners to live near their work. In 1911 there were 1,114 people living in Gwalia. They weren’t all British (the preferred immigrant profile) – there were also immigrants from Europe, particularly Italy and Yugoslavia, where the economic situation was especially difficult. Many hopefuls came from China too, but they were heavily discriminated against. Some immigrants went home, but more stayed, through generations. For example the Mazza family from Italy ran the store for decades.

Sometimes Italian or Yugoslav workers would be brought in at lower wages by the mine bosses when the miners were threatening to strike for higher wages or better conditions. That’s what Herbert Hoover did (later US president 1929-33) when he was mine manager in Gwalia in 1898. He cut wages and workers’ rights drastically. (But not his own design for the manager’s house, see below…)

It was a pretty hard life altogether, but in the 1890s another plague fell on them – typhoid. Thousands died in the Goldfields, with the dreadfully unhygienic conditions, and too many people and animals crammed together in huge filthy camps, e.g. at Kalgoorlie, on the “Golden Mile”. I visited a nearby cemetery and it was harrowing to see the number of young people who died then*. The dangers of the mine below, and more dangers above, and an unforgiving land as their home. As Hoover himself said, “A land of red dust, black flies and white heat.”

The township now has a nearby museum to the old mine itself (which recently reopened), and the surrounding community has tried to protect and partially restore the homes. I’ll leave you with some of the pictures – sad, and at the same time beautiful (in their own way) , but more than that, the cottages stand witness to the character and resourcefulness of these resilient folk in the hard early years.

*Barrachd ma dheidhinn an seo / more about the cemetery here: https://www.facebook.com/kirkmichaeltrust/posts/pfbid02pPLTegQDk4wrGJrit9SHqg9jrKgFsdcTKAmA9jprxgwgoRDNu7omwYvjnhZmcLQMl