Taigh-staile Toulvaddie

Bha cothrom agam o chionn ghoirid tadhal air àite tarraingeach dìreach air cùl nam bailtean, meanbh-thaigh-staile ùr, Toulvaddie, faisg air Easter Airfield. Rinn mi agallamh leis an stèidheadair, agus fhuair mi a-mach gu bheil rudan annasach gu leòr a thaobh an taigh-staile seo.

Sa chiad àite, ‘s e boireannach a stèidhich e, Heather Nelson, bho theaghlach tuathanach às an sgìre – a chiad bhoireannach a rinn seo o chionn Helen Cumming ann an Cardhu ann an 1811. Bha Heather ag obair ann an dreuchd gu tur eile, mar cho-stèidheadair companaidh-riochdachaidh telebhisein còmhla ris an duine aice, Bobby, ach bha riamh aisling aice an t-uisge-beatha aice fhèin a chruthachadh. Mar a thuirt i, chuir e iongnadh oirre dè cho eadar-dhealaichte ‘s a tha blas gach uile uisge-beatha, ged nach eil ach na h-aon trì grìdheidean (uisge, eòrna is beirm) anns gach seòrsa. Bha i airson faighinn a-mach dè na cothroman a bhiodh aice sin a stiùireadh i fhèin. Bha ceum aice ann an Ceimigeachd, ach san eadar-àm fhuair i teisteanasan ann an grùdaireachd is stailigeadh.

Tha boireannaich eile ag obair ann an saoghal uisge-beatha san latha an-diugh, ach chan eil tè eile ann a stiùireas am pròiseas gu lèir, mar a nì Heather, no a tha an sàs anns an obair phractaigeach aig gach ceum, bho ròghnachadh an eòrna gu cur leubailean air na botail. Tha an dealas, an cùram agus a’ mhoit aice follaiseach.

An darna rud a tha cho inntinneach, ‘s e gun do thog Heather agus an teaghlach aice an taigh-staile gu ìre mhòr iad fhèin. Tha e air làrach HMS Owl, raon-adhair an nèibhidh san Darna Chogadh, far an robh uair tuathanas beag Toulvaddie a bha le ginealaichean na bu tràithe teaghlach Heather. (Thàinig an t-ainm às a’ Ghàidhlig toll a’ mhadaidh.) Air sgàth dàlach a thaobh cead-planaidh agus le clìoradh an làraich, agus dàlach a bharrachd le Covid a dh’adhbharaich trioblaidean le stuth-togail is call cheann-latha le companaidhean-togail, b’ fheudar dhan teaghlach an obair a dhèanamh iad fhèin – drèanaichean a chladhadh, ùrlaran a leagail, ballachan a thogail agus fiù ‘s mullach an togalaich-riochdachaidh a chur suas: ionnsachadh le bhith ga dhèanamh. Faodaidh sibh na ceumannan uile fhaicinn air làrach-lìn an taigh-staile. Euchd fìor dhrùidhteach – ach bha na tuathanaich (mar na h-iasgairean) riamh cleachte ri an làmh a chur ri obair sam bith.

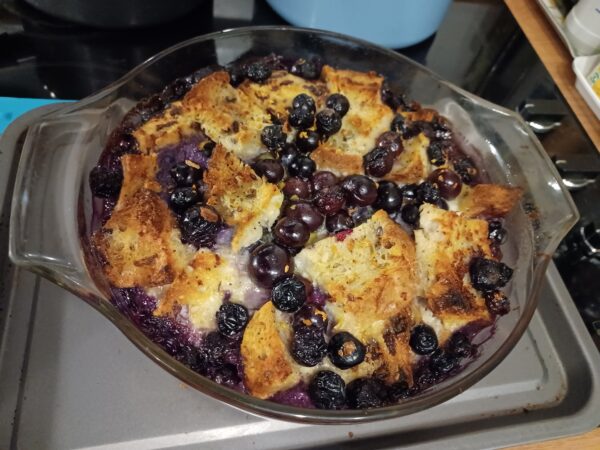

A-nis tha an taigh-staile ag obair is fosgailte dhan phoball, is iad uile gan cumail a’ dol ann an dòighean eile. Tha an obair-riochdachaidh agus am bar beag san aon talla mhòr, air a dhealabhachadh gu grinn. Tha measgachadh stàillinn deàrrsaich, fiodha is copair fìor àlainn, agus tha cuimhneachain thlachdmhor nan làithean a dh’fhalbh ann, le deasg seann-fhasanta agus caibineat-taisbeanaidh fiodha. Tha Heather gu math mothachail air ar dualchas stailigidh agus an geall air na dòighean-obrach traidiseanta aithneachadh – le gach rud air a dhèanamh a làimh. Chan eil dad meacanaigeach an seo. Gheibh gach ceum ùine gu leòr cuideachd, gus leigeil leis an spiorad leasachadh gu buileach. ‘S e cridhe an taigh-staile a tha anns an dà stail copair, làmh-òrdairichte, beag ach àlainn.

Ged a bheir e ùine mhòr gus am bi a chiad mhac na braiche abaich is anns a’ bhotal, tha an spiorad ùr-dhèanta ri fhaighinn mar-thà. Tha na baraillean daraich, làn uisge-beatha braiche ag aoiseachadh, gan stòradh air an làrach agus faodar an ceannachd is glèidheadh ro làimh.

Bidh sibh a’ faighinn fiosrachadh mionaideach mu eachdraidh an taigh-staile agus mu mar a nithar an t-uisge-beatha nuair a bhucas sibh fear de na tursan fìor phearsanta aca – faodaidh mi am moladh. A bharrachd air am bar beag anns an talla, tha gàrradh snog agus beingean is bùird a-muigh. Tha e math gnothachas-teaghlaich traidiseanta den leithid fhaicinn san sgìre againn, am meadhan tìr òir an eòrna Rois an Ear.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Toulvaddie Distillery

I recently had the chance to visit a fascinating place right behind the Seaboard Villages, close to Easter Airfield – a new micro-distillery, Toulvaddie. I interviewed the founder and discovered there are quite a few unusual features about this distillery.

The first is that it was founded by a woman, Heather Nelson, from a farming family in the area – the first woman to do this since Helen Cumming of Cardhu in 1811. Heather was working in a different field altogether, as co-founder of a television production compamy with her husband Bobby, but she always dreamed of creating her own whisky. As she says, it fascinated her how different the taste of every single whisky is, although they all have only the same three ingredients – water, barley and yeast. She wanted to find out how she could influence this herself. She had already studied chemistry, but in the meantime she has gained qualifications in brewing and distilling.

There are other women working in the whisky industry nowadays, but none of them is in complete charge of the whole process, nor themselves doing the practical work at each stage as Heather is, everything from selecting the barley to labelling the bottles. Her passion, care and pride in her product are evident.

The second unusual thing is that Heather and her family basically built the distillery themselves. It’s on the site of the former naval airbase HMS Owl, and previously was on the small farm of Toulvaddie owned by earlier generations of Heather’s family. (The name comes from Gaelic toll a’ mhadaidh, and means hound’s, or possibly wolf’s, den.) Due to delays in planning permission and clearing the site, and then Covid meaning further delays with materials, and lost slots with contractors, the family ended up digging drains, laying floors, putting up the walls and even roofing the production building, learning on the job. You can follow the various stages on their website. An impressive achievement – but then farming (and fishing) folk are used to turning their hand to anything.

Now the distillery is in full operation and open to the public, still keeping them all busy. The production, along with a small bar, is all in the one big hall, and is beautifully laid out. The mixture of gleaming steel, wood, and copper is very attractive, and there are charming reminders of the past in the old desk and the wooden display cabinet. Heather is very aware of tradition and keen to do things in a way that pays tribute to the old days of distilling, everything done by hand. Nothing here is mechanical. Each stage is also given plenty of time, allowing the spirit to develop fully. The two hand-hammered copper pot stills are the heart of the distillery, small but beautiful.

Although it will take time to mature and bottle the first bottles of malt, the new-make spirit is available to buy already. The oak casks with the maturing malt are being stored on site and can themselves be bought in advance.

You’ll get the full details of the story of the distillery and how the whisky is made during one of their very personal tours – I can highly recommend them. As well as the small bar on site, there’s a lovely garden and seating area outside. It’s good to see a family business in this traditional industry established in our own local area, surrounded by the golden Easter Ross barley fields.

www.toulvaddiedistillery.com Tel. 01862 808138.